In 2007, when I was a brand new flight instructor at Oklahoma State University, I had an experience that changed the way I looked at flying forever. While instructing in a Cessna 152 with a student who had (maybe) five hours of flight time, we experienced a partial engine failure.

For those new to aviation, there’s a glossary at the end to help with terms you might not be familiar with.

The Deadstick Day

I remember the day vividly.

My student was conducting her first pre-flight inspections on her own. Watching from the flight center window, I felt confident in her abilities—she was sharp, attentive, and had a tendency to look at me like I was an idiot, after I over-explained relatively simple concepts. As she came back in, I ran back to my cubicle and pretended that I hadn’t been watching the preflight inspection from the window. She gave the all-clear, though I double-checked the oil and fuel, and we went through the Pre-Start Checklist.

As we taxied out to Runway 17 in Stillwater, OK (KSWO) we were well-aware of a wind shear advisory in effect. It’s important to note, wind shear doesn’t always mean drastic shifts in wind direction. That day, for instance, ground winds were only 10 knots, but at 3,000 feet, they reached 40-45 knots. With this in mind, I opted to fly to our East practice area. I figured we could get there fast, perform the maneuvers in the syllabus, and spend the painful flight back to SWO talking about what we’d done.

In no time, thanks to our increased ground speed, we reached our practice spot, roughly 7 to 10 miles east of the field. At 3,500 feet, we started with basic maneuvers. Climbs, descents, turns, steep turns, etc., but as I was getting ready to walk her through her first power-on stall, the engine RPM’s began to fluctuate.

Initially, we registered a 200 RPM decrease from cruise. (~2300 RPM) I immediately took the controls and turned back toward the airport, but since we still had partial power and a monster headwind, I didn’t want to pitch for best glide… yet. I began to run through the standard L-check/restart flow.

(For you non-cessna pilots: Fuel Selector: ON, Mixture: RICH, Throttle: AS REQUIRED, Carb Heat: ON, Magnetos (Key): BOTH, and Primer: IN & LOCKED)

By the time I completed this, I registered two things: this was happening and we couldn’t fix it.

I made a call to Stillwater Tower (SWOT) and let them know what was going on. I remember them offering me, “any part of the airport you can use.” But as our engine surged erratically between 1,500 and 1,800 RPM (and then lower) I realized we wouldn’t be able to make it back to the airport. I kept heading West, my logic at the time was that I didn’t want emergency services to go on a scavenger hunt and I wanted to get as close to the city as possible.

I remember what it felt like when the realization of what was happening set in. The best comparison I can make, and this is certainly apples and oranges, is being called on in class when the teacher knows you’re not paying attention, putting you on the spot. My face heated up, my breathing got faster, and my mind went blank. I’ll say this though, I had some damn good instructors over the years, including one that would just randomly go on a “Whatever it takes!” rant when teaching emergencies. The benefit of drilling for something hundreds of times though, at least for me, is that it significantly reduces the amount of time it takes to recover from the “Element of Surprise.”

Scanning for that “perfect field” to land in, I remember thinking, “Where did all the East-West fields go?” When I found one, we crossed mid-field to make a right downwind. Around this time, my student looked at me and asked, “Are we going to be okay?” I said something smart-aleck to the effect of: “Don’t worry, I’m a professional.” I’d also like to emphasize that I said this more for myself than for her, because I needed the reminder.

I made sure to come in with some extra airspeed; I was afraid of undershooting due to nerves. The landing might’ve been slightly hard, but it was definitely nothing the plane hadn’t seen during training sessions. I remember cows scattering and how the plane’s nose wheel jolted every time it hit a pile of… let’s just say the nose wheel needed to be cleaned.

By the time we landed, SWOT had informed emergency services and our flight center what was going on. Emergency dispatch called my cell, and I was glad that we chose to get within two miles of the city, because I had to almost walk them onto the site. In a light-hearted moment after the landing, an officer jokingly threatened to slap me with a parking ticket, which, in hindsight, was pretty funny. I think he got a blank stare.

The aftermath was a whirlwind. Media vans had already reached our flight center when we pulled up, we were advised against making any comments, and we were happy to comply. After I debriefed with my student, I met with our head of flight training, and wrote out a summary of what happened. Our Program Manager was a genuinely nice guy named Terry Hunt, who suggested I drink a big orange soda (either for shock or because GO POKES!) and get back in the saddle ASAP. I went flying the next day, and flew over the field which still had the aircraft parked in the middle of it. I remember thinking, “Why did I pick that AWFUL field to land in?!” Stress does weird things to your decision making I guess.

We later found out that we’d dropped one of the intake rocker arms, causing the valve to stick open and resulting in the cylinders next to it failing. As for the plane, it didn’t make it out of MX for quite some time.

Unfortunately, the event caused my student to decide against continuing her flight training. But, 15 years later (2022), a message from that same student popped up on my phone. She had gone back to flight training and earned her instructor certificate. To this day, I think it’s this kind of passion that makes the aviation industry unique.

Why Share These Stories?

This incident wasn’t an isolated brush with fear in my flying career. Over the years, there have been numerous occasions when I’ve scared myself or found myself in a pinch in an aircraft. Every time, I’ve replayed, talked about, and shared the events, not for bragging rights or self-deprecation, but in the vain hope that these stories might prevent others from experiencing the same.

As I kickstart this blog, I genuinely have no clue where it will lead. But I invite everyone to share their stories of fear, doubt, and/or lessons learned. It’s my hope that by sharing these narratives, with identifying details removed, we can cultivate a space of learning around “taboo” topics.

This might sound a lot like a NASA Report, and it’s certainly similar. But how many general aviation pilots really take the time to sift through the NASA Report database? How many pilots are too embarrassed, scared, or reluctant to share their stories? How many pilots truly reflect on the events that lead them into trouble? How many change their behavior?

I hope this platform can be a refreshing source of information for pilots, aviation enthusiasts, and anyone willing to learn—a source of lessons, expertise, training, and safety. No topic is off the table. Let’s never stop learning, especially the tough lessons. If even one person benefits from reading these stories among (hopefully!) thousands, it’s worth it.

Your stories, experiences, and insights can help shape a safer and more informed aviation community. We invite you to share your narratives with us. Whether it’s a close call, an unforgettable flight, or a teachable moment, your stories have the power to educate and inspire. Send your stories to stories@dead-stick.com and join our mission to continuously learn and grow in the vast world of aviation.

Glossary:

We all have to start somewhere, right? Here are some basic terms defined for those still learning.

- Deadstick: In aviation, this refers to a situation where an aircraft’s engine(s) are not producing any thrust, and the propeller is not being driven by the engine. It necessitates a glide to a landing without engine power, often called a “deadstick landing.” The term originates from the “dead” or motionless stick (propeller) when the engine is not running. Pilots are trained to manage such situations, using the aircraft’s remaining momentum and altitude for a safe landing.

- Cessna 152 or C-152: A popular two-seat, fixed-tricycle-gear, general aviation airplane primarily used for training and personal flying.

- Pre-flight inspections: A series of checks conducted by pilots before a flight to ensure the aircraft is in a condition safe for flight.

- RPM: Stands for Revolutions Per Minute, a measure of the frequency of rotation. In aviation, it’s often used to indicate the speed at which the engine’s crankshaft is spinning.

- L-check: A systematic procedure, or flow, pilots follow in an attempt to quickly correct common causes for loss of engine power.

- Wind Shear: A difference in wind speed and/or direction over a relatively short distance in the atmosphere. In aviation, it can pose a hazard during takeoff and landing, or while operating at slow airspeeds.

- NASA Report: A safety reporting system where pilots, controllers, and others can voluntarily disclose mistakes without fear of penalty, with the goal of improving aviation safety.

- SWOT: Refers to Stillwater Tower, the air traffic control facility at Stillwater Regional Airport in Oklahoma.

- CFI: Certified Flight Instructor

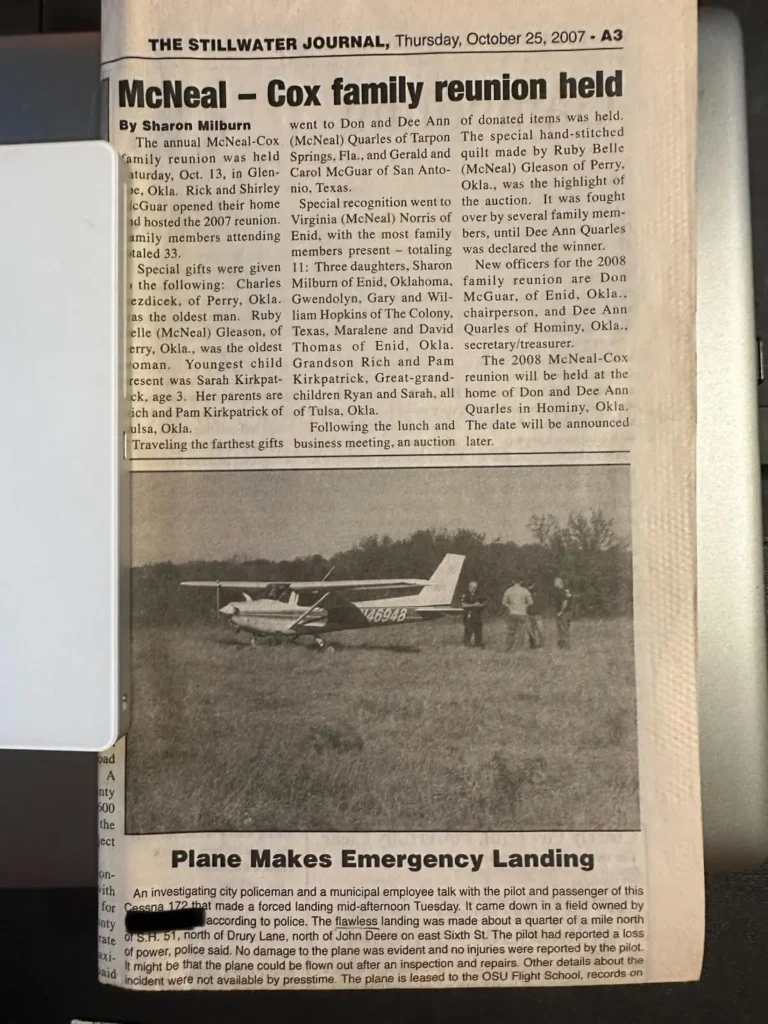

Unfortunately, these old newspapers (and my logbook) are all I have left of the incident. Additionally, it was a C-152. (Not a C-172 as stated in the article.)

0 Comments